Ancient Egyptian Ophthalmology in the Ebers Papyrus: Part 3, 'The Symptom of Inflammation in The Eye'

Analysis of several remedies in the Ebers papyrus, to identify the mysterious tntj plant, with ophthalmological analysis.

I promised you in Part 2 that you now know enough to translate many of the eye remedies in the Ebers papyrus. Allow me to prove it. We shall now skip to remedy #353 (don’t worry, we can do the others at a later date).

Disclaimer: I have published an abridged version of the following analysis in Eye which you can access here, but the journal’s word count means I can only explain all of my arguments in finer detail here, so read on and enjoy!

For my Eye article, I put together an interlinear translation of remedy #353. It includes a scan of the original papyrus, transcription into hieroglyphs, transliteration, and translation. I’ll insert it here to save time:

Since it’s all in one figure, I didn’t flip the text back to front like in the previous articles. Also note that yes, I made a mistake here. I said read from ‘left to right’ when it is, of course, ‘right to left’. Doctors regularly make this mistake in everyday life. We get so accustomed to calling the right side of an X-ray the left that we incorrectly do the same for images outside of a medical imaging context. I know for a fact I’m not the only one, honest!

As for the abbreviations in my figure, Det. is determinative. Lig. is ligature (see Part 1). P.c. is phonetic complement (again, see Part 1 if you don’t remember what this is).

Now look through the remedy. If you’ve been following Part 1 and 2, there’s only four words you didn’t already know:

swsh, meaning something like ‘symptom’, derived from the verb ‘to twist’.

taw, meaning ‘heat’ as you can guess from the bonfire determinative.

prt tntj, ‘the product of tntj’ which will become the focus of this article.

What’s interesting is that this remedy is prescribed for the symptom of heat (see the scribe’s annotation). This is the only eye remedy in the Ebers papyrus that words it in this way. The other similar remedies are simply for ‘heat in the eyes’. And there are so many remedies for ‘heat in the eyes’, that it probably refers to a red, painful eye, because this is a common presentation of many eye diseases. A red eye is just a response to inflammation; it’s a dilation of the conjunctival blood vessels.

I must emphasise this because older translations say that ‘heat in the eyes’ is blepharitis (inflammation of the eyelids), which seems illogical to me given the sheer diversity of remedies for ‘heat in the eyes’. And blepharitis only rarely causes a red eye. In fact, the diversity of treatments for ‘heat in the eyes’ in the Ebers papyrus implies that ancient Egyptian physicians must have exercised clinical acumen not otherwise documented in the papyrus. They must have distinguished between causes of ‘heat in the eyes’ so as to select the appropriate remedy. For example, one of the remedies seems obviously to be a lubricant, which would therefore be appropriate for red eye as a result of dry eye diseases. Alternatively, a charlatan could’ve prescribed something merely for the symptom of heat in the eyes. What do I mean by that?

Today, it’s apparently common in America for patients to use ephedrine eye drops to conceal the symptoms of red eye. How? Ephedrine causes constriction of the blood vessels in the conjunctiva by triggering your adrenaline receptors. Red eye becomes white eye. This is useful if, for example, you are about to attend a wedding and need to look your best for the photographs. It’s also useful if you know you have a self-resolving condition, such as a viral conjunctivitis, but don’t want to look ill. In such a case, concealing the redness is not harmful. However, unless you have a diagnosis, hiding from the problem is clearly a bad move, assuming you want to be able to see things ever again.

We do actually use a related drug in clinical practice to constrict the surface blood vessels on purpose. Phenylephrine 10% will blanch the redness of the eye in a condition called episcleritis, but do nothing in the case of scleritis, so it allows us to differentiate between the two. Only the superficial vessels of the episclera (the surface layer of the whites of the eyes) will blanch with 10% phenylephrine. The deeper, chunkier, blood vessels of the underlying sclera (the whites of the eyes) will not be affected.

So which of this remedy’s ingredients could have done the same thing? It’s so specific a description that we must search for a pharmacologically active ingredient. It’s not galena. It’s certainly not the carob pod paste, which again seems to be acting as a binding agent. There is but one ingredient left to discuss.

The tntj plant

First, we have the word, prt, which literally means 'that which comes forth' because it’s really just a form of the verb pr, ‘to emerge'.

In this context, it’s therefore translated as fruit or seed. The reason for me highlighting this translational nuance will soon become clear.

Then follows the name of the plant: tntj. You can transliterate it as tnti. It’s just a difference in transliteration styles. It comes with pill and plural determinatives, so you know it’s an ingredient. In summary, the product of the tntj plant, one dose of it.

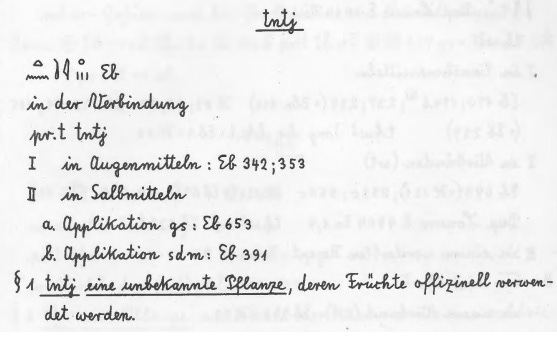

I'm going to be honest with you. Egyptologists don’t know what this plant is. Nobody seems to have even made any suggestions. One of the defining books in its genre, the Wörterbuch der Ägyptischen Drogennamen, has only this to say about tntj:

So nothing useful. Even more annoyingly, this isn't the only remedy that lists it as an ingredient in the Ebers papyrus. It also never appears in any other papyrus. The Ebers is all we’ve got for tntj.

So what do we do? Let’s look at those other instances of use. They might tell us what tntj is.

First, let's look at a remedy I skipped over. I skipped it because in Part 1, I decided to start with one that’s easier to use as an introduction, that one for the ‘whitenings’ in the eyes, Ebers #347. But the eye remedies in the Ebers papyrus actually start at remedy #336 and end with #436.

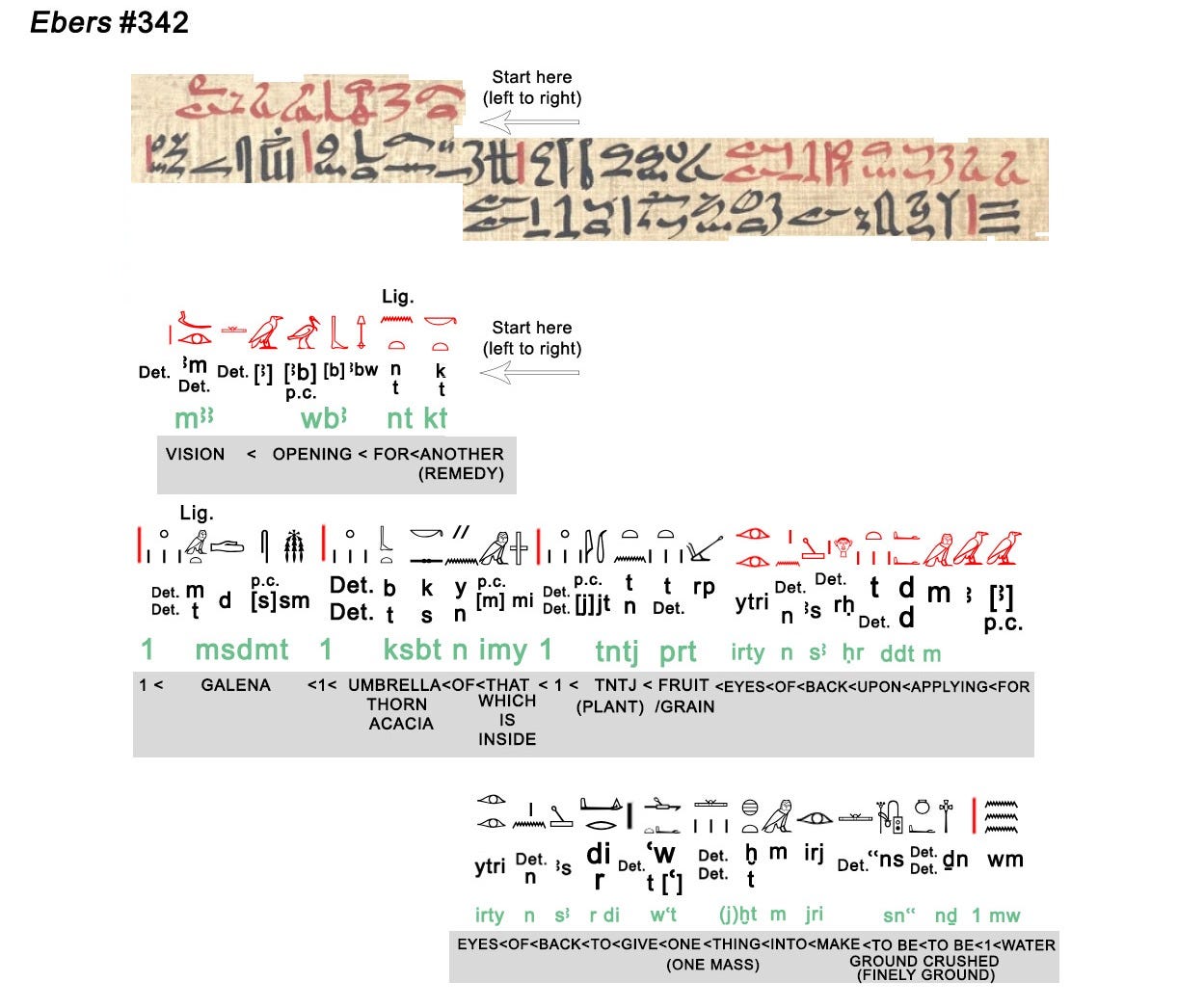

Ebers #342

We’re going to look at #342, which also contains the product of tntj. Here is part of the same figure I made for my Eye article:

A few notes here about the heading:

wba is the verb ‘to open’ or ‘to drill’ when the subject is stone, so here it must be to open. The determinative is a scroll signifying an idea or other abstraction.

m ddt. The glyph of the two arms is a special way of writing the infinitive, ddt, of the verb rdi 'give'. But what does m plus the infinitive mean? Well, here it is a type of what's called a pseudo-verbal construction, and this one usually denotes a progressive or future action. The context here probably implies progressive, so this is best translated as 'for applyING' hr sa n irty, upon the back of the eyes.

This is a remedy for ‘opening’ the vision. Is that just a poetic way of saying to improve one's visual acuity? We know it can't be because other remedies specifically say they are for eliminating ‘cloudiness’ in the eye, such as #339, or ‘blindness’, as in #356. ‘Opening the vision’ must mean something else. The most obvious answer is that opening the vision is a literal description of dilating the pupil, or at least, improving the vision swiftly.

Guess what? That's the other use for phenylephrine in modern ophthalmology. Every adult in an ophthalmology clinic who needs their pupils dilating so we can have a proper look at the back of their eyes receives two eye drops: tropicamide and phenylephrine. Even if the Egyptian physician’s real aim was to swiftly improve vision, pupil dilation might be seen as affecting such a wish. Mydriasis (the posh name for pupil dilation) enhances brightness and peripheral vision in conditions of dim lighting.

And indeed, first on the list of ingredients for remedy #342, for [probably] dilating the pupil, we see prt tntj, one dose. The other ingredients are imi n, ‘that which in inside of’, probably better translated as ‘the innards of’, the ksbt. Egyptologists think ksbt might be the wood of the umbrella thorn acacia (Vachellia tortilis), or at least some other similar tree because there are usages where the ht, or ‘wood’, of the ksbt is described. But the qualities of the wood are debated. So one dose of that, then we’ve got our old friend msdmt, which I remind you is galena, one dose, and mu, which is water. Last, you’ve got instructions for use. Needless to say, none of the other ingredients would affect the pupil or visual acuity, so the culprit must be whatever is in the tntj.

Other tntj remedies

So it’s looking like tntj is a plant that produces a drug similar to phenylephrine or ephedrine, something that stimulates the sympathetic nervous system, responsible for ‘fight or flight’. Now, apart from the two remedies we’ve mentioned, the tntj is called for in only two other remedies in the Ebers papyrus. The two other mentions are Ebers #391, a remedy for ‘eliminating a cold in the head’, and Ebers #653, which is a remedy for providing relief to the sinuses. Ring any bells? Yep. In the modern world, pseudoephedrine, which is closely related to phenylephrine, has long been used to treat a stuffy or blocked nose. The drug causes constriction of the blood vessels in the nasal cavity, thereby reducing production of mucus.

The identity of the tntj plant

To summarise then, tntj is used for three things in the Ebers papyrus: dilating the pupil, reducing conjunctival hyperaemia (i.e. redness of the eye), and drying up nasal mucosa. These are all the actions of an alpha adrenergic agonist (i.e. a drug that targets particular adrenaline receptors) such as phenylephrine. Whatever tntj is then, it must be a plant that produces something similar to phenylephrine, an alkaloid such as ephedrine or pseudoephedrine.

I reckon the most promising candidate, considering geographic distributions, is Ephedra alata. It’s native to north Africa.

Note that this is a non-flowering and therefore non-fruiting plant, a gymnosperm, so must we translate prt as grain or seed rather than fruit? Well, the seeds, or more correctly in the case of Ephedra, spores, don’t yield much alkaloid so probably not. So what is this prt then?

Gymnosperms like Ephedra have reproductive parts called pollen strobili, which are closely related to the pinecones of conifers, but are fleshy enough they might even look like fruit to the untrained eye. They do contain the alkaloids we’re interested in, so there you go.

The use of an Ephedra species for medicinal purposes is not unknown in antiquity. An extract called ephedra has been used in traditional Chinese medicine for at least 2000 years, in which it is known as ma huang. We know because it's mentioned in The Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing (神农本草经), which is the oldest surviving written record of Chinese medicines, thought to have been compiled in the 1st or 2nd Century AD. If the ancient Egyptians did know about ephedra, it's certainly feasible they may have learnt of it from Chinese doctors. We know trade existed between the two civilizations because Chinese silk has been found on Egyptian mummies from around 1000 BC.

But these traditions never call for drugs to be extracted from the pollen strobili of Ephedra. The alkaloids are most concentrated in the stems and leaves. And this is why I laboured the point about the derivation of the word prt. A better translation in this context is probably neither fruit nor seed, but ‘extract’.

Based on these ideas, one might offer two other candidates for tntj: mandrake and henbane. Mandrake was not native to Egypt but was known through trade with levantine cultures. However, there's a much better candidate Egyptian word for mandrake anyway: rrmt. Henbane was native to Egypt and there’s no better candidate word for it. So why not henbane? Both candidates have a major problem in my eyes: neither plants produce sympathomimetics (drugs that stimulate the sympathetic nervous system, ‘fight or flight’). They produce anticholinergics instead (i.e. drugs that inhibit the parasympathetic nervous system, ‘rest and digest’), mainly scopolamine and atropine, which will certainly dilate a pupil but won't directly cause constriction of blood vessels. Anticholinergics can sometimes cause a mild constriction of the blood vessels indirectly, as a reflex to the vessel dilation they actually cause, but nothing like the effect of, say, phenylephrine. In other words, they won't reliably make a red eye any less red.

In conclusion, the best candidate for tntj is a species of Ephedra, probably Ephedra alata. So that is one mystery solved, albeit a small one that nobody else seems to have ever cared about.

Hopefully, you now realise one of the aims of this project is to clear up some mysteries within the Ebers papyrus. And now that you’re hopefully comfortable looking at hieroglyphs, we can start to explore some more mysterious remedies and ingredients. Can we solve anything else? Stay tuned for Part 4!