Ancient Egyptian Ophthalmology in the Ebers Papyrus: Part 2, 'Blood in The Eyes'

Translating Ebers remedy #348, with ophthalmological analysis.

If you understood part 1, you now grasp the basics of how to read an ancient Egyptian manuscript. But you need practice. Last time, we looked at remedy #347 in the Ebers papyrus. Where else next to read then #348?

Ebers #348

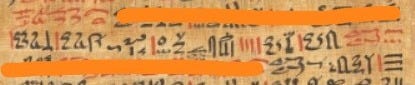

Here’s the scan of the original papyrus:

I’ve erased the surrounding text so you don’t get distracted. Remember to read right to left from the red text, which you hopefully remember is the heading.

Now, let’s flip it from left to right so it’s more intuitive for a native English reader, and transcribe into standard hieroglyphs so it’s easier to read.

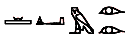

First, the heading:

kt ‘another’ [remedy]

nt ‘for’

dr ‘removing’

Yes, those first three words are the same as in the previous remedy. But from thereon it’s all different.

snf (three uniliteral glyphs, top to bottom)

followed by two determinatives: one of a fluid pouring from lips, because snf translates as ‘blood’, and the three vertical lines indicating plurality. Yes, blood is plural.

m (the owl glyph) ‘in’

irty ‘the eyes’. (middle Egyptian had no definite article, so you can insert ‘the’ wherever you think it appropriate)

So, all together: ‘Another [remedy] for removing blood in the eyes’.

What might that mean then? You might guess it means a red, painful eye, since this is the presentation of many eye diseases, but I heavily doubt it does mean this because, spoiler alert, many of the other remedies specifically target eye inflammation.

So it probably means one of two conditions:

Subconjunctival haemorrhage, which as the name suggests, is blood underneath the conjunctiva.

Hyphaema, which is blood inside the front (i.e. anterior) chamber of the eye.

Subconjunctival haemorrhages are a heck of a lot more common, because even rubbing your eye a little too vigorously can cause one. The conjunctiva is suffused with a fine web of blood vessels, and they’re a little fragile so it doesn’t take much to pop them. In modern times, the other common association is high blood pressure, but I doubt many ancient Egyptians would’ve had a problem with blood pressure because their diets would’ve comprised much less salt than ours, and that’s the main contributor. However, in a sandy environment, you’d probably rub your eyes more, so you might be more prone to a subconjunctival haemorrhage. What about the other thing I mentioned then? Well, a hyphaema, in contrast, is the result of eye trauma, hopefully a lot rarer. I can't rule it out though.

Now, let's look at the remedy itself and see if we can find any more clues. First ingredient:

That first glyph relates to writing or things to do with writing, and its got the pill (circle) and plural determinatives. The triliteral writing glyph can be read as sha but from the w (the swirl glyph) phonetic complement after it, we can tell that it’s being used for its other reading here, chru (like the ch in cheese), which is some type of red ochre— what the ancient Egyptians used for ink. Yellow ochre is a mixture of clay, sand and ferric oxide. Red ochre is what happens when you heat it up, but you can find naturally red ochres too if they contain lots of ground haematite. Egyptologists are unsure about exactly what type of ochre this chru is. Doesn't matter too much. Look again and you’ll see we have one vertical red stroke meaning one dose of it.

Then the next ingredient is waju. The four vertical red strokes indicate four dosages of it. To clarify, the first tie-like glyph is the triliteral waj and the swirl-like glyph is w/u.

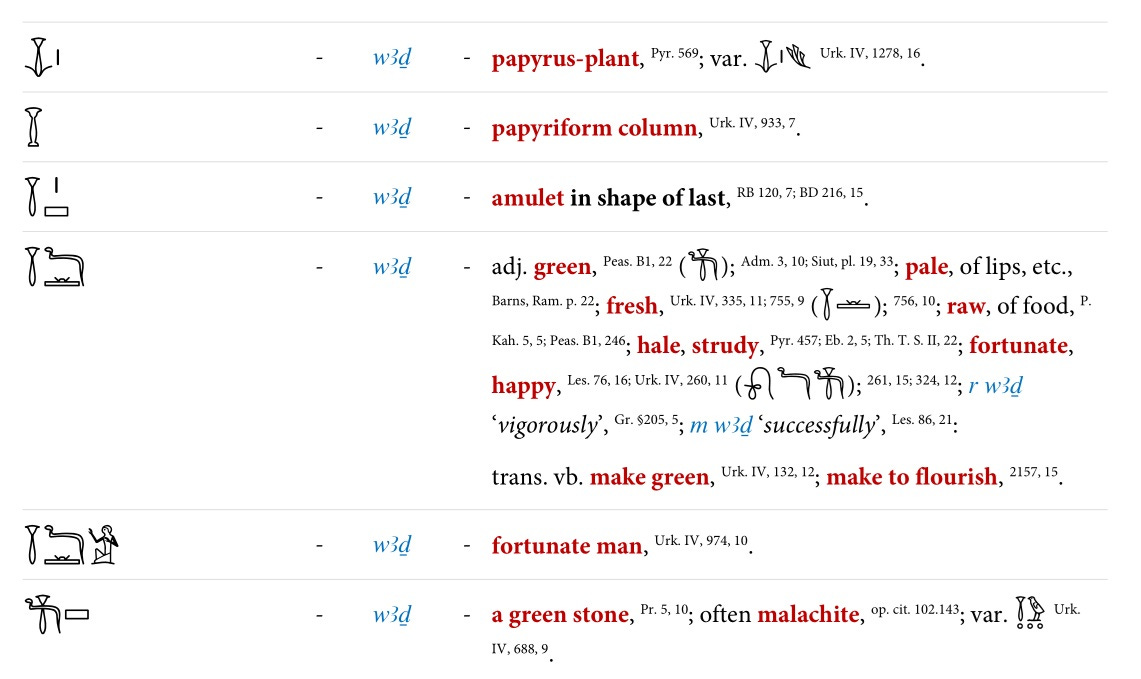

waj is actually the colour green, as Faulkner’s dictionary tells us.

The u at the end transforms it into a plural masculine noun, hence the plural determinative of the three vertical lines, so waju literally translates as ‘the greens’. It’s also got the pill determinative so we know it’s an ingredient. As Faulkner’s dictionary entry above confirms, in this context, ‘the greens’ therefore refers to malachite, the mineral form of copper carbonate. The ancient Egyptians used it for green eye paint.

The next ingredient is msdmt with the pill and plural determinative. One red stroke means one dosage.

To clarify, the first glyph is the biliteral ms, followed by a phonetic complement, s. Then the hand is the uniliteral d, the owl is m, and the bun is t.

Now this word derives from the verb, sdm, meaning ‘to put make up on’.

Take this verb. Apply an m prefix to transform it into a noun. Then add a t at the end, the feminine suffix, because msdmt is a feminine noun. Put all of this together and the most accurate translation of msdmt is the make-up we call kohl, a kind of ancient eyeshadow still used today in many parts of the world.

Kohl is, as you might guess, an Arabic loanword (كحل kuḥl), because by ‘many parts of the world’, I primarily mean the Arabic world. Interestingly, this Arabic word derives from the Aramaic, kuḥla

Note well: this word does not bear any resemblance to msdmt, and this difference serves as a reminder for you that ancient Egyptian is not a semitic language, despite what one might naturally assume. It’s in the Afro-asiatic family.

Linguistics aside, the principle component of kohl is galena, the mineral form of lead sulfide, so msdmt often just gets translated as galena. Occasionally, you see it translated as stibnite, the mineral form of antimony trisulfide, because stibnite was the primary ingredient of kohl in other areas of the Mediterranean. However, scientists have analysed ancient Egyptian kohl, discovered within the original application tubes, buried in ancient Egyptian tombs, so we know they mainly used galena and other lead-based compounds. Look at this finely preserved artefact! The kohl-stick itself is on the side.

For the next ingredient in the remedy, the first glyph looks like a tree branch.

It's the biliteral glyph ht, with a phonetic complement t (the bun glyph). Recall that the single vertical line determinative tells you to read it as the actual thing. Yes, ht means ‘wood’.

This is followed by an adjective, awa, which is derived from the verb meaning ‘to rot’ or ‘to spoil’. The lasso glyph is the biliteral, wa, and the Egyptian vulture is a phonetic complement.

Then we’ve got the usual pill and plural determinatives, plus one stroke for one dosage. This positioning also confirms for us that awa was actually just an adjective and not something separate.

We think this ‘rotten wood’ is probably the Egyptian term for petrified wood, a particularly beautiful type of fossil wood, dating back to the Carboniferous epoch.

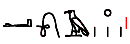

The next ingredient is jart. One dose of that.

The translation of jart is slightly contested, with three main candidates as far as my research goes:

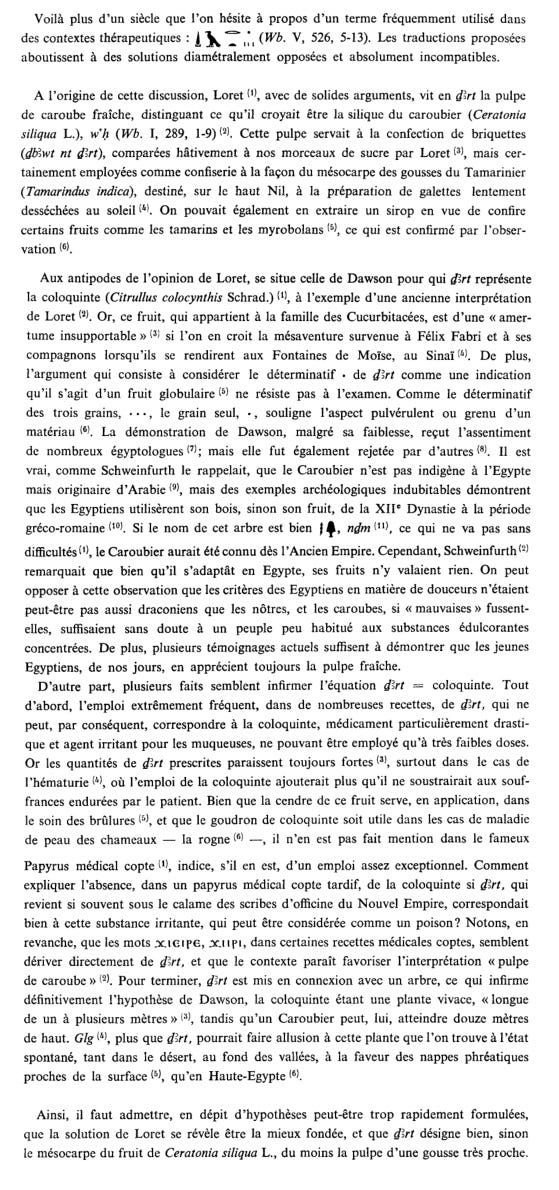

The pulp from a carob pod. The Carob (Ceratonia siliqua) is a tall Mediterranean tree. Ground carob pods are still used together as a culinary alternative to cocoa, and to soothe stomach aches. This is the translation for jart provided in Manniche’s An Ancient Egyptian Herbal (page 91-2), the most popular reference text for these things. If you want the full argument, Aufrére’s analysis in études de lexicologie et d’histoire naturelle III is persuasive:

Colocynth (Citrullus colocynthis), also known as bitter apple. This is the competing hypothesis in Aufrére’s analysis, which he thinks isn’t as likely as carob pod pulp. Based on the properties of processed colocynth, I also wouldn’t want its extract anywhere near my eyes.

Ammoniacum gum (Ferula ammoniacum). Bit of a wildcard, this one. Montserrat argues via analogy to a different Egyptian drug called shrt (direct quote):

When studying shrt the sequence we follow is:

We are looking for an Egyptian drug to be identified with the silphium- Ferula assafoetida.

We know its physical and pharmaceutical properties.

We know its geographical origin from foreign countries located in Asia, and beyond the western

desert.

An interesting fact is that we know the Coptic name of the Ferula assafoetida: [Coptic word] .

We establish the hypothesis [Coptic word]; to be the Egyptian shrt.

We consider our hypothesis confirmed by:

The study of the determinatives of shrt.

The study of the pharmaceutical properties of shrt.

The texts mentioning the high value of shrt.

The texts mentioning the foreign origin, specially from western countries, of shrt.

When studying DArt the sequence we follow is:

We know the term of a drug in Egyptian.

We notice that it was prescribed instead of the silphium-Ferula assafoetida-shrt because its

pharmaceutical properties are similar.

We establish the hypothesis DArt to be the ammoniac gum.

We consider our hypothesis confirmed by:

The study of the determinatives of DArt.

The study of the physical and pharmaceutical properties of DArt.

The origin of both drugs from the western desert.

The Coptic term, jart, for the ammoniac gum is the transcription of DArt.

In other words, the argument for ammoniacum gum seems to be a couple of perceived similarities between the uses of jart and the uses of the semi-mythical herb, silphium of Cyrene, whose identity still confounds scholars today (although it was prized by the ancient Romans). Montserrat believes jart was used as a substitute for the rarer silphium, making ammoniacum the most likely candidate. These similarities do not make a good argument, as the same argument could be made for many herbs. His one good argument, as far as I can tell, is the Coptic word for ammoniacum gum:

This is pronounced ‘chart’ (the ch sound from loch). Coptic was the ‘last’ stage in the evolution of the Egyptian language, before the Arab conquest of Egypt eventually relegated it to a purely liturgical language. This means Coptic provides vital clues into the workings of ancient Egyptian linguistics. In fact, Champollion’s knowledge of Coptic was the key that allowed him to finally decipher the mystery of hieroglyphs.

In comparison, the Coptic word for a seed pod, particularly that of a carob is:

This is pronounced ‘dieire’. However, the Coptic for the Carob tree itself is:

This is pronounced ‘carate’, and seems to have been a semitic loanword (e.g. Akkadian or Aramaic). So I don’t think the Coptic argument goes in favour of ammoniacum gum either.

In conclusion, the most likely identity for jart is the pulp from a carob pod. Having gone through the various uses of jart in the Ebers papyrus myself, this seems most likely to me too.

The last ingredient in the remedy is water, transliterated as mu. Unsurprisingly, the Egyptians represented water like this:

One red stroke so one dose.

What follows are the instructions for usage. The first glyph is the biliteral nj.

As a verb, it can mean ‘ask’ or ‘grind’. With this determinative of an arm holding a stick and another one of a jar, it means ‘grind’. Then it’s followed by the writing glyph again, and the scroll determinative telling you this is the idea of writing rather than a verb or something else (the scroll is the general determinative for an abstraction), so you want to grind the thing fine like pigments used in ink. Hence, this is usually translated as ‘pulverise’.

Then we have di, ‘to give or apply’, and m irty, in the eyes.

So to recap the full recipe, ‘one part chru-ochre, four parts malachite, one part galena, one part petrified wood, one part carob pod pulp, one part water. pulverise and apply to the eyes’.

Might this remedy be effective for ‘blood in the eyes’?

Would this do anything for a haemorrhage, either subconjunctival or within the anterior chamber? No. but it doesn’t matter because these things resolve on their own without treatment anyway. A subconjunctival haemorrhage usually clears up within a few weeks, for example. So the patient might well think their doctor has done a good job. If, on the other hand, the patient sustained a traumatic eye injury leading to a hyphaema, there may well be other problems which wouldn't resolve without proper treatment. We might therefore surmise this remedy was probably given for a subconjunctival haemorrhage only, because, as I said, then it doesn't matter what you give as long as it's not overly harmful.

Let's explore those ingredients in greater detail anyway, because as you’ll see in future articles, they’re used in many other ancient Egyptian eye remedies.

Galena

Galena, the mineral form of lead sulfide, comes up a lot in the Ebers papyrus insofar as eye diseases are concerned. The ancient Egyptians really trusted galena to soothe an inflamed eye. One problem: it's toxic. And although lead sulfide is not soluble in water so might not be so terrible when applied to skin, the fine powder could still stick to the fingertips and be ingested in that way. Lead poisoning has certainly been diagnosed in users of kohl in modern times. But it's not all bad news for kohl users. A study in 2010 demonstrated that lead compounds stimulate the production of nitric oxide in skin cells. Nitric oxide is an important immune system modulator. So perhaps it did help soothe inflammation. And from a practical point of view, the dark eyeshadow also protected the eyes from the sun’s glare.

Malachite

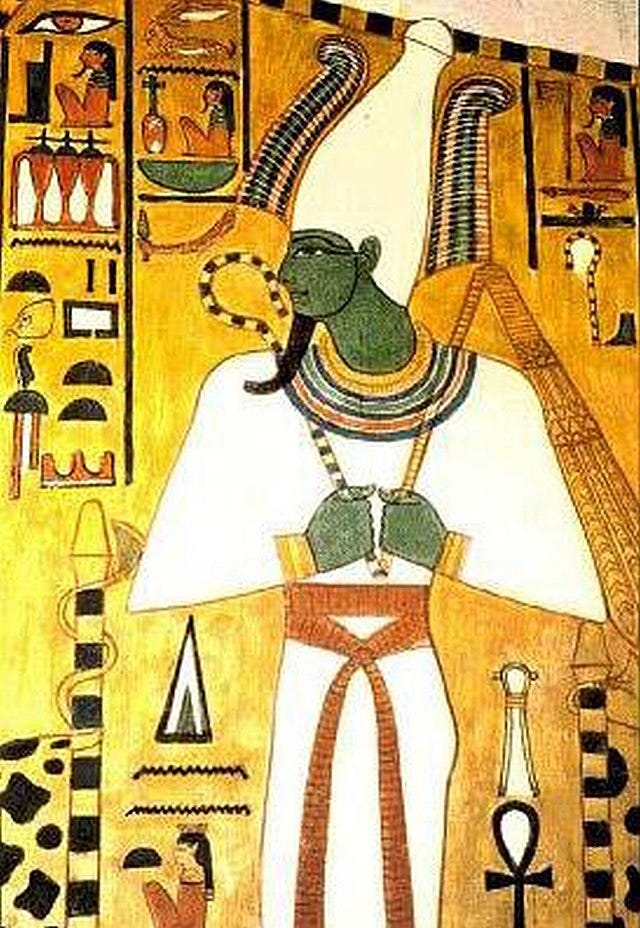

Now what about malachite, the mineral form of copper carbonate? Copper is well known to possess antimicrobial properties, and even kills multi-drug-resistant bacteria, so it definitely would’ve warded off bacterial infections. The ancient Egyptians hit the nail on the head with this one. There's also a symbolic element to it. The colour green was associated with fertility and life. Osiris, the god of the afterlife, was often depicted with green skin for this very reason.

Petrified wood

The petrified wood is, when all is said and done, just stone. Fossilised wood, which was plentiful in the land of Egypt. Non-academic sources suggest that ancient Egyptians prized petrified wood for funerary rites or amulets but there isn’t any archaeological evidence to support this. The hardened wood might have symbolised stability and permanence. But it wouldn't have done anything useful for the eyes. The other possibility is that it might have been used for the abrasiveness of the powder, possibly helping drug absorption. But it definitely has no pharmacological activity.

Carob Pod Pulp, Ochre, Water

These are seeds from the carob tree and they're apparently quite tasty. Carob pods were also used as a binding agent in various pastes, so that’s probably what it’s doing in this recipe, along with the ochre and water. In modern terminology then, we would say that galena and malachite are the active ingredients. Who knows what the petrified wood was doing. Magical power-up?

Conclusion

In summary, we have a prescription for probably (hopefully!) a subconjunctival haemorrhage, a condition which self-resolves. But lots of interesting ingredients which tell us a lot about ancient Egyptian medicinal beliefs. And these ingredients come up time and time again in the Ebers papyrus. You may find this surprising, but this means you now have enough knowledge to translate the recipes for most of the other Ebers eye remedies. Don’t believe me? Wait for Part 3!