Ancient Egyptian Ophthalmology in the Ebers Papyrus: Part 1, 'Whitenings' of The Eyes

An introduction to Egyptian Hieroglyphs, the Ebers Papyrus, and a translation of a remedy for an eye disease, with ophthalmological analysis.

Introduction

Who am I and what is the aim of this article?

My name is David and I’m an eye surgeon whose been learning the language of ancient Egypt, specifically middle Egyptian, for the best part of a year now. This is because I’m a massive nerd. It was therefore inevitable I would end up translating medical papyri at some point. In this article, I'm going to show you how to read hieroglyphs, so I can show you how to translate parts of the Ebers papyrus, the largest and most complete medical papyrus ever discovered. Specifically, I'm going to translate some of its remedies for eye diseases, since that's where my interest lies. My aim is then to analyse these ancient Egyptian remedies from a medical point of view, because, spoiler alert, the published translations by non-medically qualified Egyptologists are definitely a bit off. As a result, I've solved a couple of minor mysteries. I first published some of my work in Eye this year, which you can access here.

What is the Ebers papyrus?

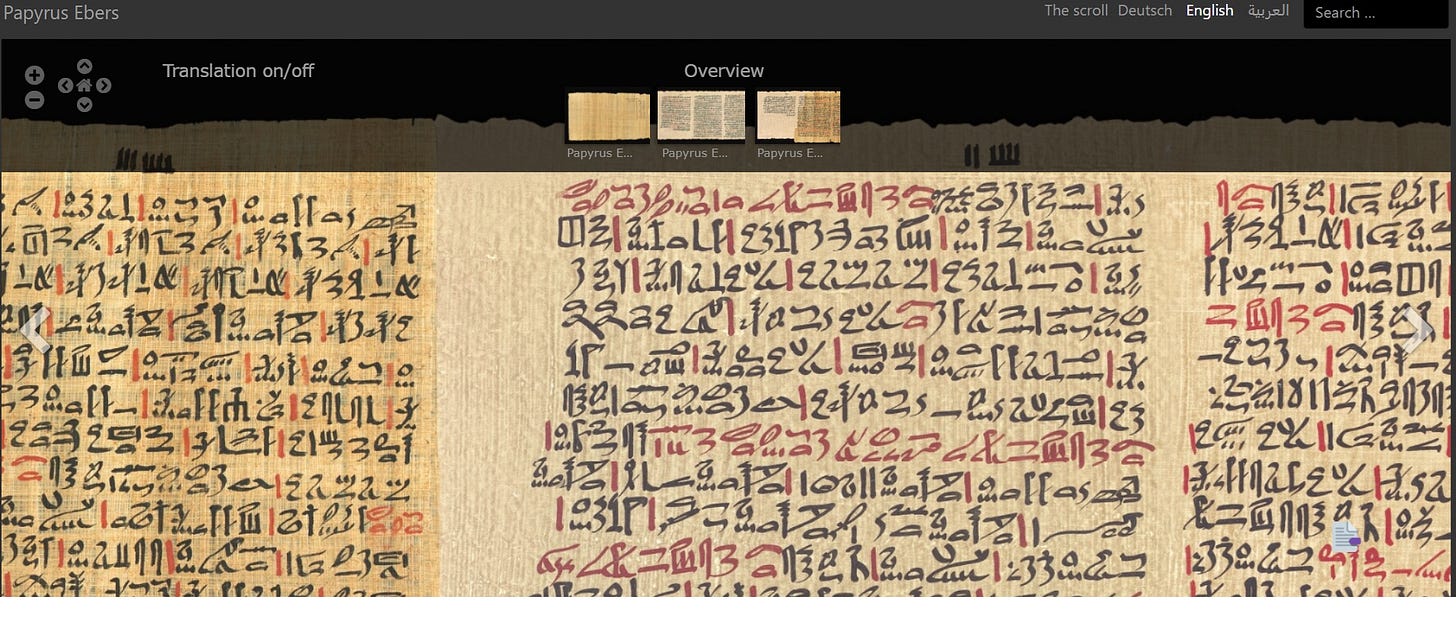

The Ebers papyrus is an ancient Egyptian medical text named after George Ebers, a German professor, who purchased it in the late 1800s. He was told it came from the Theban necropolis but nobody knows for sure where it was originally discovered. Doesn’t matter too much though because it’s 20 meters long, 110 pages, and contains around 700 remedies, making it the most comprehensive medical papyrus still around. Today, it's housed at the University of Leipzig, but you can access a digitized version online, which is what I'm going to use.

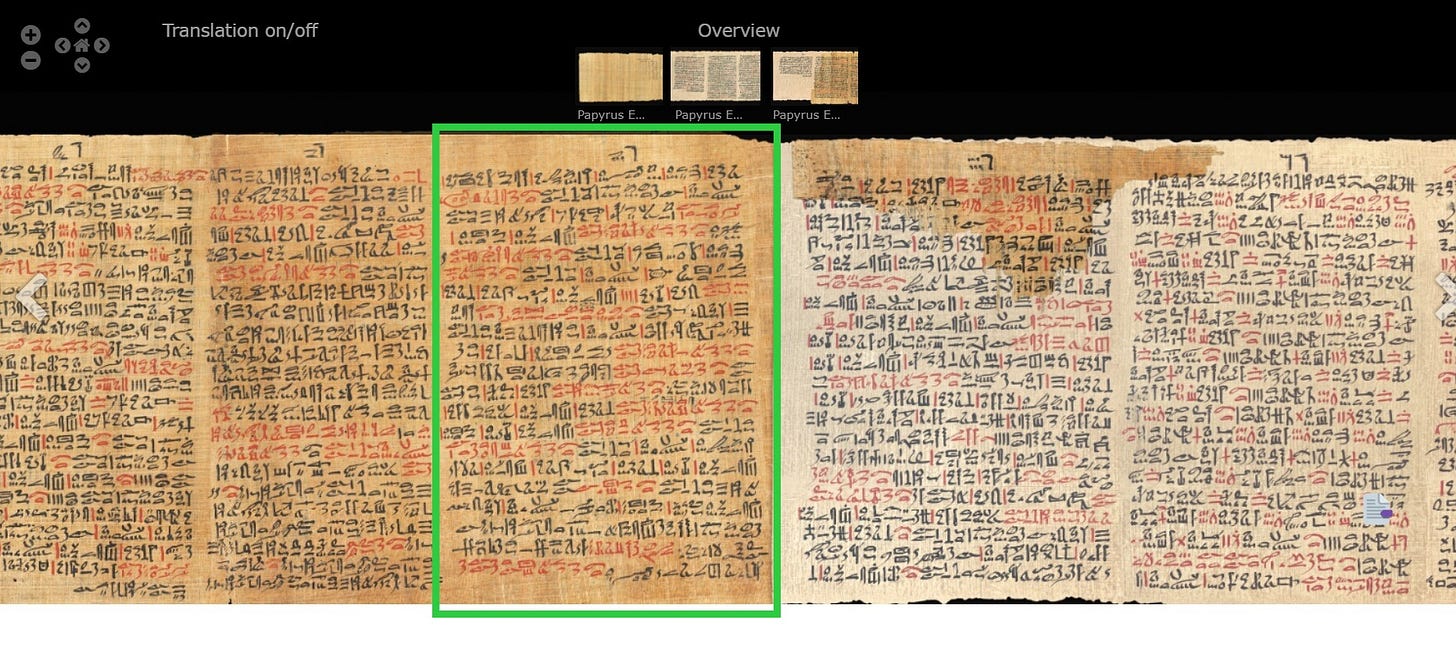

Here it is (if you didn’t bother to click the link yourself):

It’s long. That’s just a section of it. Now let’s zoom in further.

You might now be wondering: where are all the hieroglyphs? Well, you're looking at them, kind of. The Ebers papyrus, as with most papyri, was written in the hieratic script, which is the handwritten, cursive form of the famous Egyptian hieroglyphs. Since hieroglyphs comprise intricate pictures, which are effortful to draw properly, this extremely cursive form was more practical for everyday use by scribes, accountants, priests, whatever. However, their cursive nature does mean it's more difficult to interpret for us non-ancient folk.

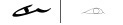

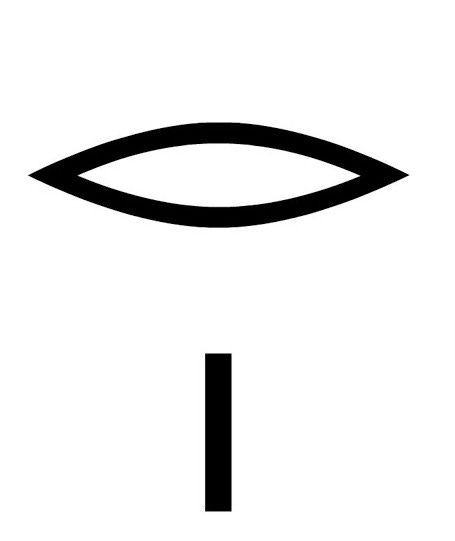

For example, you can see that this glyph is obviously an eye (hieratic on the left, hieroglyph on the right):

Unless you're well versed in hieratic though, this next one isn't so obvious. It's actually a water glyph— one of the most common.

Before I start translating though, you're not going to understand what I'm talking about if I don't explain two basic things.

(1) how to pronounce ancient Egyptian words.

(2) how Egyptian hieroglyphs work, which is actually quick and easy to understand. It's the grammar that’s a bother to learn, and you can leave that to me.

Of course, if you do understand these things, just skip the next two sections.

How to pronounce Ancient Egyptian

I’m going to be honest: we don't know how ancient Egyptian words were pronounced. We've made educated guesses about many words (see Allen’s fascinating book, Ancient Egyptian Phonology), but certainly not enough for anyone to revive the language. The main reason: Egyptians never wrote down any vowels, as in Hebrew or Arabic. Imagine I wrote, ‘HLL MY NM S DVD’. You could learn what each word means but you wouldn't know how to actually say them out loud. And you wouldn't be able to tell many words apart either, except by guessing from their context. However, Egyptologists do need to say the words out loud so they can talk about them at conferences and what-have-you, so they use what's known as the modern Egyptological pronunciation. In short, this means arbitrarily adding as many 'e' sounds as you need to make a word pronounceable.

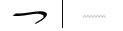

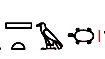

For example, look at this glyph (hieratic on left, hieroglyph on right):

It’s meaning is 'god', and we pronounce it netjer, although that’s certainly not how the ancient Egyptians pronounced it. The middle Egyptian language, so called because it was spoken in the middle kingdom period of ancient Egypt, also has a number of sounds not used in English, most notably four types of h sounds, distinguished by various dots and braces.

There's also this:

The ‘3’-like symbol is a glottal-stop, which you can just write or pronounce as a. Don’t forget though: it’s not a vowel. Also, if you’re wondering, the bird is an Egyptian vulture. Ornithology is crucial to learning Hieroglyphs. I assure you: this is not as much of a joke as you are hoping.

Now look at this glyph:

That apostrophe-like symbol makes a back-of-the-throat awww sound, like the ayin in Arabic (also in biblical but no longer in modern Hebrew— blame Yiddish speakers). Again, Egyptologists tend to pronounce this simply as a. You don't have to worry about pronouncing these correctly though. You just need to know what it means when I show you these symbols.

How hieroglyphs work

The second thing I need to explain: how hieroglyphs work. It's simple. There are only four types of hieroglyphs:

Those that make one sound, called uniliteral.

Those that make two sounds, called biliteral.

Those that make 3 sounds (such as the nṯr glyph i just showed you, pronounced netjer), called triliteral.

Those that don’t make any sound at all, because they are silent tags on the end of a word which tell you what kind of thing the word is (e.g. animal, vegetable, mineral). This is called a determinative.

The determinative is important because you can have two words spelt the same way but meaning different things. For example, here are three uniliteral (i.e. one-sound) glyphs that spell out yaw.

The determinative at the end is an old man with a cane because that’s what yaw means here: an old man. But when it has this other determinative—

yaw instead means ‘praise’.

The ancient Egyptians obviously pronounced the two words differently, but when you've only got the consonants, you need those determinatives to tell you which of the two words you're dealing with.

There's only two determinatives I want you to memorise and the rest I'll tell you as I go along.

A single vertical line means that instead of reading a glyph as its sound, you read it as the object represented by the glyph.

For example, you read this glyph as the single sound r:

But when combined with the single vertical line, you translate it as the word ‘mouth’.

The other determinative I want you to know is the three vertical lines, which tell you the thing is plural (hieratic provided here as well because it looks annoyingly different).

The last thing I want you to know about hieroglyphs is that often, when you have a biliteral glyph, it'll be followed by one or more uniliteral glyphs that appear to repeat the last sounds of the first glyph, but are actually silent.

For example, look at these glyphs:

The top glyph here is mn and the bottom one is just n (the water glyph). But the uniliteral is silent. you just read it as mn, not mnn. The silent glyph is called a phonetic complement, and the aim is to help make the text (1) easier to read, and (2) aesthetically more appealing. They're also useful when you have biliteral glyphs that can make multiple sounds, because the phonetic complement tells you which one to read.

For example, the first glyph here is a biliteral that can either make the sound ab or mr:

In this word, the phonetic complement that follows is a b (the foot) so you know the first glyph is pronounced ab, the full word being abju, the ancient name for the city of Abydos. That cross-in-a-circle is the determinative for a town.

Then look at this word:

Here, you have alternative phonetic complements, m (owl) and r (mouth), so you know to use the first glyph's other possible reading, mr, and the full word is just mr, meaning ‘pyramid’. And yes, that pyramid determinative at the end is a bit of a give-away.

You can also get phonetic complements for triliteral glyphs. For example, the first glyph here is the triliteral glyph, nfr. It’s supposed to be a heart and trachea, apparently. Don’t ask.

The two uniliterals next to it are f (horned viper) and r (mouth), both phonetic complements. So you just read the whole thing as nfr. This is a super common word because it means ‘perfect’, ‘good’ or ‘beautiful’.

That’s enough of that now. Let’s dive into the Ebers papyrus.

Into The Ebers Papyrus: The Eye Book

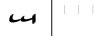

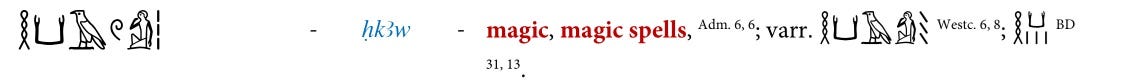

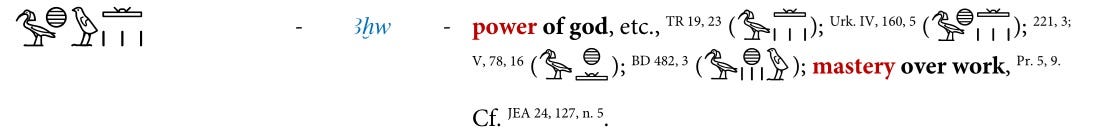

The Ebers papyrus begins with some general incantations that are useful for a wide variety of medical matters. ‘Incantations’ because ancient Egyptian medicine was heavily intertwined with magic. The ancient Egyptians thought of magic, which they called hka

…as the art of causing action via indirect means, usually through speaking with ‘effectiveness’, or ahu

And most importantly, anybody could do it if they knew the correct words. Actually, magic remained intertwined with medicine right up until the renaissance. No self-respecting medieval doctor was ignorant of astrology, for example. So that's important. I'm going to skip the introductory medical spells though, like what to say when unravelling bandages, because we don’t care about that in this article. We want to delve straight into the ophthalmology. Was that the royal ‘we’? No! By reading this article, you implicitly agreed to be a fellow eye nerd.

So we'll start by zooming in on the section of the Ebers papyrus that deals with eye diseases: page 57.

The number is at the top here. Interestingly, page numbers are rare in Egyptian papyri. But the Egyptians had a hieratic glyph for every number so when they do show up, they're easy to read.

Note that numerals in the original hieroglyphs you see on temple walls are configured in a completely different way, but we don’t care about that in this article.

Also note that as we can see the page on the right is 56, we can immediately tell the papyrus is written from right to left, which was very common in ancient Egypt.

Now, let’s start you off with this remedy, which is the 347th remedy in the whole book. I think it’s a good one to introduce you to how we go about translating this stuff.

Ebers #347

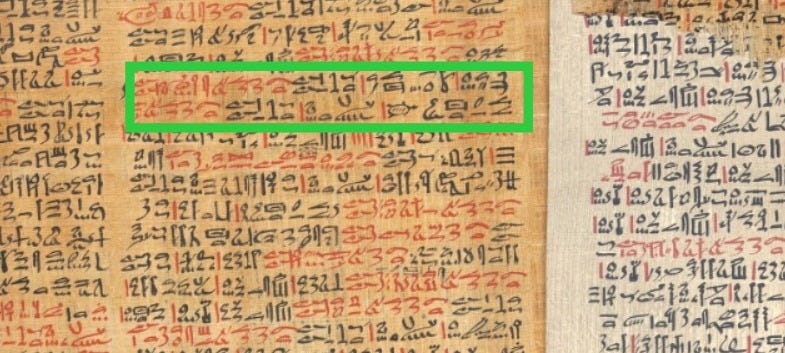

How do I know this is the start, you might now be wondering. The ancient Egyptians didn't have capital letters or punctuation. If they wanted to make some text stand out, they just used red ink. Usually, this red ink, or rubric, signifies headings, which makes it a lot easier to navigate a papyrus. The other use for red ink in the Ebers papyrus is for writing dosages, as you'll soon see. So those glyphs in red ink at the top left of my annotation rectangle are the title of the 347th remedy.

And here is this section transcribed into standard hieroglyphs, which, as I said, are a lot easier to read than their hieratic counterparts.

This transcription has also been flipped around so you can read it left to right, this being more intuitive for native English speakers. The heading (red ink) says:

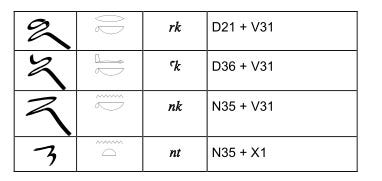

kt ‘another’

nt ‘for’

Note the joined-up glyphs for both of these words in the hieratic, if you look back at the scan of the original papyrus. These are called ligatures, and they’re common, well, because they're quicker to write. Here are some of the most common ligatures:

Next is dr with a determinative of a man striking with a stick, because this is a verb meaning ‘remove’ or ‘repulse’

Then we have shd with the determinative for colour (two concentric circles), because hd means white and the s is the causative prefix so together it means something like 'made white' or 'brighten' or 'illuminate'.

Faulkner’s dictionary agrees:

Then, looking back at the text, it has the plural determinative so you can translate it as something like 'the whitenings'.

nw ‘of’

And, last, the two eyes which is transliterated as irty, unsurprisingly meaning ‘the eyes’.

The ty ending signifies the feminine dual plural. You never have more than two eyes so you're only ever going to use a dual plural, as in other languages which have a dual plural form.

So all together, this heading translates as 'another for removing whitenings of the eyes.’ Another what? Remedy, of course. Most of the headings start with the word ‘another’ and don’t bother to say what it is another of because it’s obvious. This is a book of remedies.

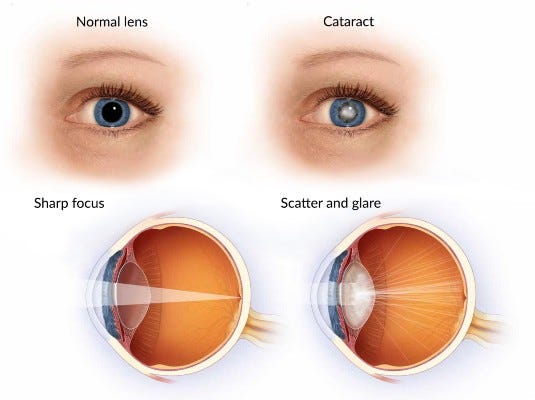

So the question is, What does it mean by ‘whitenings’ of the eye?

According to previous translations, there are two possible answers.

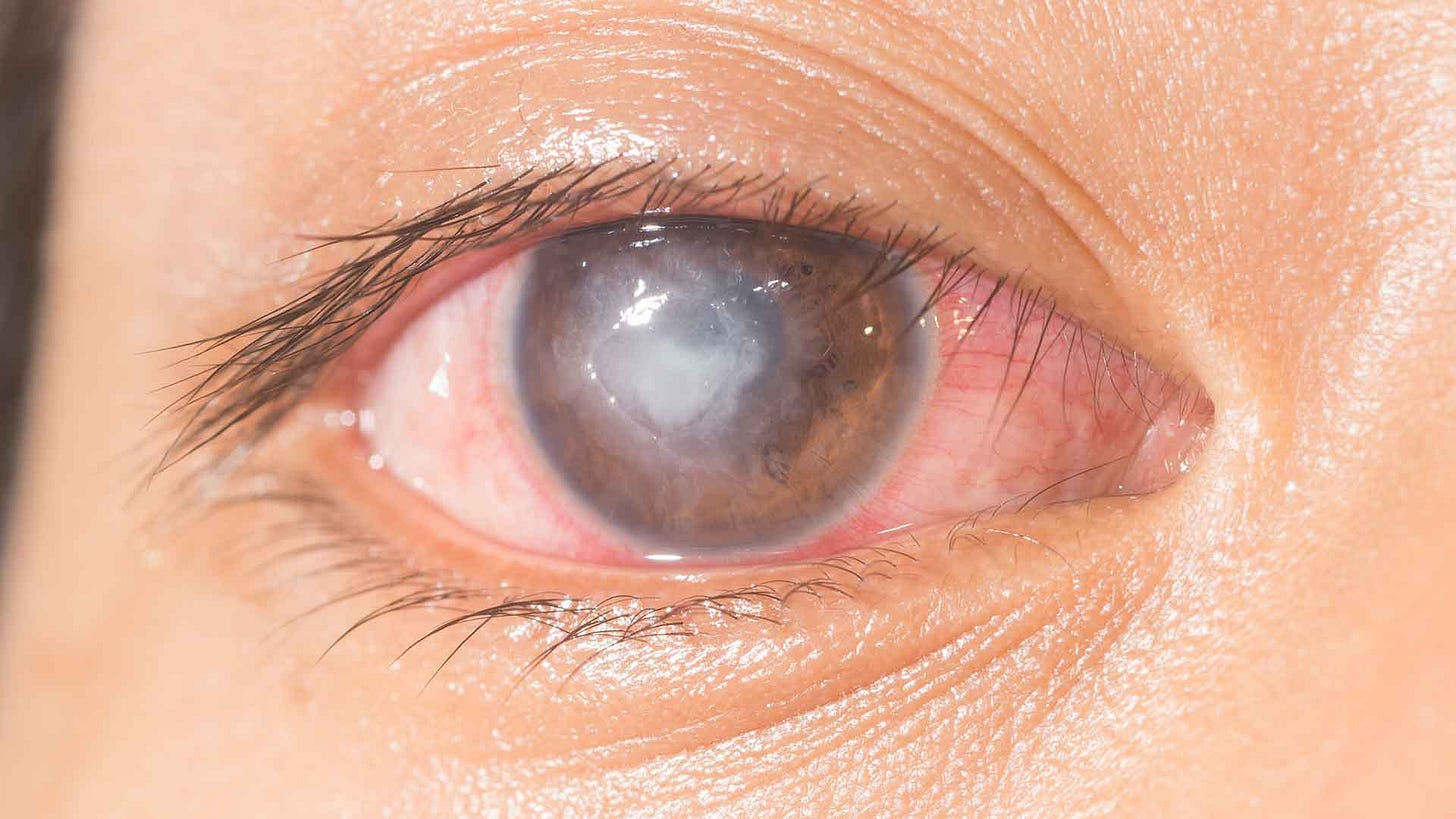

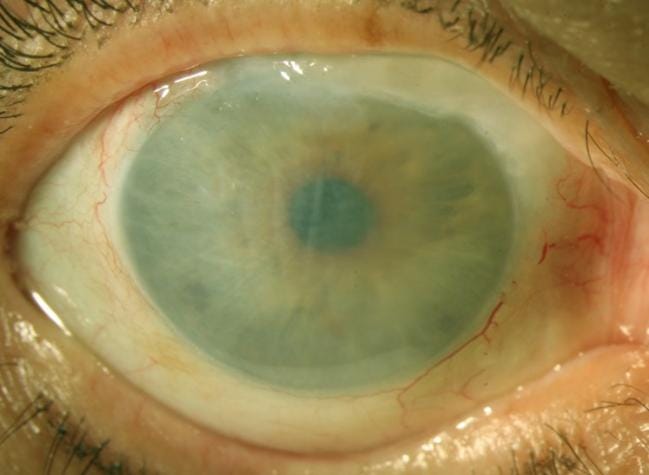

Cataract, which is a cloudiness of the lens inside the eye, usually the result of advanced age although many other diseases can cause it.

An opacity of the cornea, which is the transparent front window of the eye. A white patch on the cornea could be an active infection or just a scar from a previous infection.

There's actually a third option which no translator has ever mentioned but I'll talk about that afterwards. For now, let's stick with cataracts and corneal ulcers. So how can we tell what the answer is?

Well, let's see what the ingredients of the remedy are and then we can decide. I say this because an extremely important thing to remember is: not many eye diseases are fatal. It follows that if you were a doctor in ancient Egypt who wanted to keep the money rolling in, you needed to solve your patients’ problems, or they wouldn't come back to you in the future. They certainly wouldn't recommend your services to their mates if you messed up their eyes. So how will knowing that help us? Well, for a standard age-related cataract, we don’t know of any efficacious drug at all. The only cure for a cataract is surgery. So if the papyrus isn’t going to recommend surgery, we can be reasonably sure the whiteness doesn't refer to cataracts. A placebo effect will only take you so far. If you’ve got a cataract, no fumbling about with sugar pills will improve your vision. You need surgery and yes, we do have evidence surgery was performed for cataracts in the ancient world, the earliest form being known as couching. So let's see what the Ebers papyrus says for the remedy itself.

The first word of the remedy is wdd with the determinative for a piece of flesh (looks a bit like a comma). Note I have omitted the first glyph w below because it was on the previous line and I’m lazy. This word means ‘gall bladder’ or ‘bile’, which is the liquid inside a gall bladder.

n ‘of’

shta (triliteral) is, as you can probably guess from the determinative, a tortoise.

So, bile of a tortoise. And a red vertical stroke meaning ‘one dose’.

Then we have a glyph of a bee with an adjacent t (the bread bun glyph)— a phonetic complement. The determinative is a little medicine pot and the three lines of plurality. Yep, this means honey. And again we have one red stroke.

Then it says di which is the verb ‘give’, here meaning ‘apply’.

Then r which has many translations all broadly meaning 'with respect to', but I should probably show you the dictionary entry anyway to prove it.

Sa (the glyph that looks a bit like a printer) with the single vertical line determinative, meaning ‘the back’

And you can also see:

n, ‘of’

and irty again (‘eyes’).

So the full translation is ‘apply to the back of the eyes a mix that is one part tortoise bile and one part honey’.

Apply to the ‘back’ of the eye?

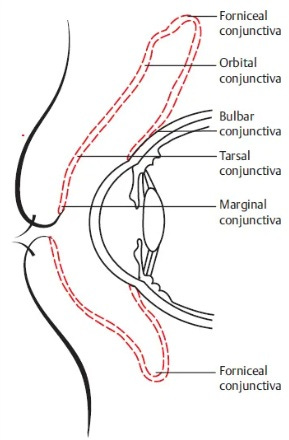

Before we look at this recipe properly, let's talk about what it means by 'apply to the back of the eyes’ because this is going to come up a lot. It's a literal translation, by the way: the ‘back’ of something. The published translations tend to put ‘back’ in quote marks because its not clear how this would work for an eye. You clearly can’t put anything behind the eye because of the conjunctiva, which is this baggy membrane here:

As an aside, this is why you should never believe anybody who claims to have lost a contact lens ‘behind’ the eye. The conjunctiva prevents such a tragedy. Instead, the contact lens just gets stuck underneath the upper eyelid.

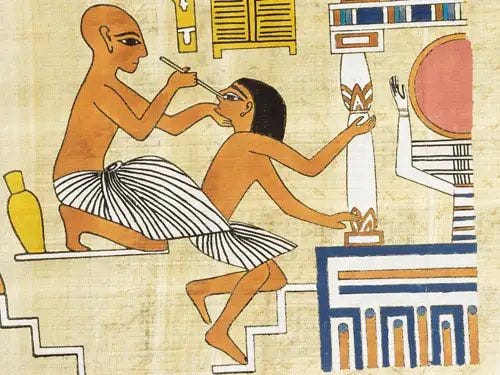

So what does it mean then? Well, some Egyptologists have translated it as 'the upper eyelid'. But i think we find a good clue in one of the few ancient Egyptian illustrations of an eye doctor at work.

This is a painting copied from the tomb of ipwy at Thebes. Some scholars have interpreted it as the couching surgery I mentioned earlier, but it’s probably not because the tool isn't reaching inside the eye. This eye doctor has a pot next to him and is clearly applying some ointment, and if you look closely, he’s applying it between the eyeball and the eyelid. In more technical terms, he’s placing it in the lower conjunctival sac. That’s how we apply eye ointments today. You pull down the lid and squirt the ointment inside.

It's easy to see how this ‘inside’ area could be described as the 'the back'. Besides, applying it to the skin of the eyelid wouldn't make any sense.

So might this remedy have been effective?

Now onto the recipe. it's clear that this concoction wouldn't do anything for a cataract, but would it do anything for a corneal ulcer, that is, an infection of the cornea?

Honey

Everybody’s favourite bee juice in particular has long been known to have antimicrobial properties. It just contains so much glucose that the high osmotic pressure would draw out the water from any bacterial cell immediately and kill it. That’s why honey lasts so long at the back of your cupboard. But the big question is, would honey be enough to treat a corneal ulcer?

In the modern world, absolutely not. 95% of corneal ulcers today are associated with contact lens wear, with the most common bacterium being Pseudomonas aeruginosa. You need a reasonably broad-spectrum antibiotic to have any chance of killing Pseudomonas. It’s a hardy bug, resistant to all sorts, so honey just wouldn't cut it. However, the ancient Egyptians didn't wear contact lenses. The majority of their corneal ulcers were probably the result of corneal abrasions that became infected, for example, after being scratched by a cat, or more likely in a sandy environment, a foreign body.

So perhaps honey would work, but has anybody tried it? Actually, yes. It's still a traditional treatment for corneal ulcers in many parts of the world. Accordingly, there's an Iranian randomised controlled trial in which 50 patients with foreign body induced corneal ulcers were given either a 70% sterile honey-based ophthalmic formulation or 0.3% ophthalmic ciprofloxacin (a standard antibiotic treatment), every 6 hours. No significant difference was found between the two groups in terms of healing duration. Now, for a number of reasons I wont bother going into, this is not a study that’d cause me to change how I practice. Antibiotics are too good at their job. But if honey really did nothing, wouldn't we expect to find some benefit in using antibiotics compared to the honey? After all, untreated corneal ulcers can progress rapidly with devastating results. Well, it’s possible many of these foreign body induced corneal ulcers would've healed on their own without treatment. I myself have seen many contact lens associated corneal ulcers presenting to eye casualty that have already started resolving without treatment. So perhaps all this study shows, if anything, is that these particular corneal ulcers didn't need any treatment at all. But a larger and more rigorous trial might provide a more definitive answer.

It might be worth doing. There is at least some experimental evidence in animal models that honey has anti-inflammatory properties which might help an injured cornea to heal faster. And a case series demonstrated honey may help with persistent epithelial defects (i.e. corneal abrasions that are being stubborn about healing). For now though, your best bet is to consult an ophthalmologist for proper treatment.

Tortoise bile

Bile salts in general are well known to be deadly to bacteria. In fact, that’s kind of their point. It's not their only purpose, but there's a ton of evidence that bile salts kill lots of biliary pathogens. There's also a 10th-century Anglo-Saxon remedy containing ox bile, which was demonstrated to be effective. But modern scientists have not tried using bile to treat a corneal ulcer, because that’d be weird. The bacteria that cause corneal ulcers are not the same as the nasty ones that live in your gut. So the question is, why tortoise bile? Well, this probably comes down to magic. The tortoise shell is probably a symbol of protection. We know it was used in a variety of protective amulets that had nothing to do with eyes. Observe.

Some Egyptologists have speculated that the Egyptians associated the tortoise with good eyesight but there’s not much evidence for that. I myself wonder if Egyptian physicians tested different animal biles and found tortoise bile worked the best. Different animals do have different bile compositions, so it might've made a difference. But until I get around to testing the treatment myself, I can’t say for sure.

In summary, if I were stuck in ancient Egypt without modern medicines, would I want to use this treatment for a corneal ulcer? Probably. But I certainly wouldn't use it today. Please don’t try it at home.

Now, what about that third possible translation for ‘whitening’ that I mentioned earlier, which no other translator has mentioned? Well, the other whiteness of an eye that would be visible to an ancient Egyptian is corneal oedema, which is when the cornea gets swollen with water.

In modern times, we know there are lots of causes for this, so we always treat the cause first. But we can also treat the corneal oedema itself with hypertonic saline 5% drops, which osmotically draws out the water and thus improves the patients vision. It’s a temporary measure, of course, but often effective. Now, if you applied honey to the cornea instead, that would also work. High osmotic potential, remember? There’s even a case series showing that this works. So my point still stands: corneal oedema is a ‘whitening’ of the cornea that this ancient Egyptian remedy would treat successfully.

Conclusion

To summarise, we have a treatment for a corneal whitening, probably corneal ulcer or oedema, comprising a mixture of honey and tortoise bile. And more likely than not, an ancient Egyptian patient would’ve benefited. Hurray!

In the process of learning all of this, you have hopefully gained a basic understanding of how to read an ancient Egyptian manuscript. And now you know these basics, we can get into the nitty gritty of further eye remedies in Part 2. You must await Part 2. Do not go anywhere until I have written Part 2.

Now here are some buttons.